In this short series I want to share some “cooking adventures” that can help identify ways to make near substitutes without sacrifice that have the added benefit of contributing to a balanced diet rich in proteins, with sufficient fibres but a notably lower carbon content. I dedicate this recipe to my mom, my international lived experience and its dedicated to another very special person in my life. I think its about high time to share. I have been encouraged by friends to be less of a keyboard warrior for the good cause, be a bit less “shy” and share useful things more broadly with the world.

Growing up, I keep saying, jokingly, that there wasn’t much sugar in my life. I am all to aware that this joke can go places. But, my parents tried to make sure we grew up with as healthy a diet as it can get and as they could afford. Which meant: a lot of home cooking and a joy of cooking, in particular for people, that was shared. But as a kid, I did not always like this.

A stable dish growing up in Southern Germany is Spaetzle. Often in conjunction with Linsen and Spaetzle (lentils and Spaetzle), or with Sunday Roasts, preferably with a good bone roast sauce. But there was something not quite perfect about the Spaetzle. My mom used whole grain flour for the simple reason: it is more healthy (not a health claim). The added fibre is good for your digestive system and the whole grain keeps you full for longer.

But unfortunately, and that may be important for kids who know the non-whole grain version: the optics are not as ideal. They are slightly grey and just not as tasty or inviting looking.

So I went on to create a new-ish version of Spaetzle that significantly reduces the egg content, without sacrificing protein, flavour, texture, but with the benefit of the fibre that we get from the wholegrain flour. Right now, there are Gluten-free versions of Spaetzle that use chickpea flour, but not for the explicit purpose of decarbonization or making Spaetzle more healthy.

I introduce you an India-meets-Southern Germany in London dish. This is not unbefitting for the recent geopolitical pivot around the IMEC (but that is a different topic).

A nice combination: alcohol free beer, a cashew/green bean Sichuan pepper dish along with an umami dry/spicy noodle dish

Recipe

- 175 g plain white flour

- 75 g chickpea flour (primary structural protein + fibre)

- 5-10 g corn starch

- (potato starch → softer; rice starch → firmer, higher footprint)

- 1 egg (≈ 50 g)

- ~150 ml water

- Salt only in the batter (but no need, depends on what you make with the Spaetzle), not in the cooking water if serving with umami-rich sauces

- Optional: nutmeg

Mixing logic

- Combine all dry ingredients first; starch must be fully dispersed to avoid clumping.

- Add egg, then water gradually.

- Target consistency: thick, elastic, glossy; looser than pasta dough, firmer than pancake batter.

- Beat vigorously (spoon or mixer) for 1–2 minutes until bubbles appear. The work here does part of what the binding proteins in the egg does. But its really not that necessary.

Resting

- Rest batter 10–15 minutes.

- Chickpea flour hydrates slowly. Longer resting times if you use more chickpea flour and even less egg.

- Skipping this step weakens structure at low egg shares.

Cooking

- Bring water to a gentle boil.

- Do not salt the water if pairing with umami-forward sauces (mushroom, cheese, miso, soy).

- Press, scrape, or extrude batter directly into the water, there is special presses for it, you’ll find ample videos.

- Cook until pieces float, then 30 seconds longer.

- Remove with slotted spoon and drain well.

Further processing

- You can combine them further with a range of dishes

- You can freeze them and then fry them from unfrozen if making a large batch

- There is no reason why this should not work industrially to produce

Challenges of smart decarbonization along production networks

I think of this very much in line with our work on production networks as this can be used to identify pivot vectors. Or smart transitions that can help decarbonize. Trade wars are food wars (H/T Secretary Yellen). This is structurally the case because, not surprisingly, land is a predominant factor of production for food and farmers are a powerful polity in most societies and in particular so in democratic societies where land has outsized political representation. This happens mechanically e.g. through secondary chambers (think: US Senate, German second chamber of parliament, or even the EU Commission where every country gets a Commissioner in the College of Commissioners), but also politically as real estate ownership is much more concentrated among the political class.

The likelihood that a UK MP is a landlord is three times as high compared to the average UK citizen. If you think MPs develop laws that are narrowly aligned in their own self interest e.g. through giving them perks or handouts (which IMO would be a sad affair for political representation and may have downstream implications that massively skew capital allocation in our economies and societies).

- MPs with “significant rental income” (≥£10,000/year): 17%. TI-UK report (PDF), summary page

- UK “unincorporated landlords” declaring rental income in 2023–24: 2.86m. HMRC property rental income statistics

- Share with property income ≤£10,000: “nearly half”. HMRC property rental income statistics

- Total income-tax payers in 2023–24: 35.9m. HMRC income tax liabilities

But this is an aside. The end result from the above recipe does look like Spaetzle and they sure as well go very well with most dishes that you would traditionally use Spaetzle for.

This surely looks like Spaetzle?

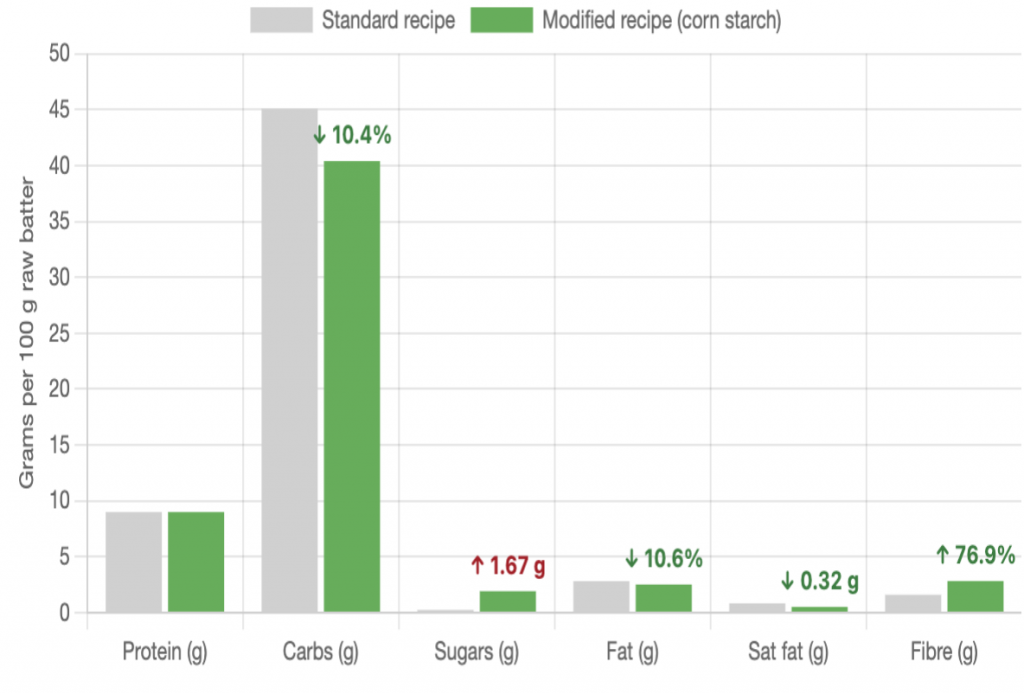

But it does get even better. Because actually this recipe may be perceived to be notably healthier in some conceptions of what healthy and wholesome looks like. Its easy to calculate the nutritional value. But it is equally easy to calculate the environmental burden and, well, the caloric value.

Normalising the standard recipe to an index of 100 allows us to see this cleanly: carbon intensity falls much faster than calories as egg share is reduced, because emissions are convex in animal inputs while caloric density is not. The modified recipe, using corn starch and chickpea flour as structural complements, lands around three quarters of the original carbon footprint while retaining more than ninety percent of the energy density per 100 g of batter.

What the figures make clear is that most of the environmental and nutritional leverage in something as banal as Spätzle does not come from heroic substitutions or purist eliminations, let alone bans, but from understanding where structure actually comes from. That is, the chemistry is what matters. And all the rest, is in my view, a social construct that we need to redefine and re-ask ourselves whether human flourishing is directed in a healthy and happy way. So you have an easy way to reduce CO2 emissions from your Spaetzle by almost 25% and even more, while also lowering the caloric intake — because let’s face it, obesity is a big problem.

Now if we look at the ingredients in terms of nutrients, it gets even better — at least, in some belief space – since we live in a world that is obsessed with Protein.

There is no trade-off but a reallocation: protein remains effectively unchanged, saturated fat falls, fibre more than doubles, and the small increase in sugars is visible precisely because the baseline was close to zero.

What matters for scaling is that egg turns out to be a threshold input: once you are above roughly five percent of total batter mass, additional egg adds richness rather than structure. Below that point, structure is carried by hydration, starch gelatinisation, chickpea protein, and mechanical mixing.

Nothing in this reformulation is fragile or bespoke: the ingredients are commodities, the rheology is compatible with existing pressing and extrusion processes, and the incentive alignment is obvious.

Lower emissions, lower cost volatility, and no need to redesign production lines. In that sense, this is not a lifestyle optimisation but a process-compatible adjustment, one that works at home, in a restaurant kitchen, and on an industrial fresh-pasta line for the same underlying reason: once you understand where structure really comes from, you stop overpaying—environmentally and nutritionally—for ingredients whose marginal contribution has already been exhausted.