I wanted to share a new project or experiment, or, in the least, lets call it a method to explain AI to folks. I am working on that I broadly call and is broadly linked to the idea of human embeddings — I had mentally deposited that idea on my social media ledger and discussed this in my lectures and class. But the term has been used in a few other settings before. For example, Anson Yu has done something similar for match-making (not group design). I see this as key to a revised form that a new way to think about labor markets and labor market reallocation could look like. I also think of this as a way to rethink teaching and how we work at universities entirely.

I may be wrong but I think at present, I find that the matching market in labor market and other domains may be far from perfect. Nevertheless, the labor market matching function has seen massive changes over the past decades due to the emergence of the internet, which should, all else equal, reduce search costs. My student, See-Yu Chan, in his job market paper, is studying the implications of improvements of the matching function through job boards (think: LinkedIn) on labor market outcomes.

The solution below is my attempt to operationalize AI for educational or group creation settings. Given the urgency of climate action, and many other domains that require cross-cutting skills and functional organisations and teams, it is IMO imperative to think about the best way to combine to create highly functional teams is flawed. I think of this as an extended way to rethink industrial policy. I am hopeful this can be taken to policy makers.

Human resource management flaws

During the pandemic many societies experienced the slowness of their bureaucracies in handling with a dynamic crisis that may have required fast build up of capabilities (Dominic Cummings seems to rant about the HR profession). I do concur though that I feel human resource management is often extremely process focused, and not actually working on ensuring there is efficient allocation of personalities, deep skills and character traits that are important for healthy and functional teams.

This is where entities like LinkedIn could come in. They host a ton of data about their underlying user base, paired with data on the CVs. Imagine squaring this with data that captures the intellectual products of the individuals involved. This could be, for example, code bases; github repositories; online artifacts such as writing and art. Ultimately, these data are incredibly informative in many ways about the latent dimensions that may be super important. And that is where I believe such data should fullfill their social function and that means: any rents that arise out of the use of such linked data that was often shared not with informed consent, should at least make sure that these rents are taxed in the communities in which said rents arise — that is: where the technology is being used.

Embeddings to fuzz language In the broadest sense embeddings can be thought of as high dimensional vector representation of pretty much any kind of data in a latent vector space that we may not be able to interpret the latent meaning of the dimensions. Embeddings are most commonly used as key building blocs to large language models and the easiest way to think about them is through word2vec representation of words as vectors. These are trained, for example, by using a skipgram objective function on large corpora of natural text. The representation of words as vectors then allows the performance of numeric calculations. That is, we can do arithmetic with words and they do seem to make “sense” in a human understanding sense.

In any case, I think human language and in particular how people engage in a structured conversation can be very helpful to infer latent dimensions that may be particularly suitable and informative to create highly functional teams. In the past I have had the experience with group work that always had elements of dysfunction. The endogenous formation of groups that often happens is problematic, as especially in multi-cultural settings, there is often clustering of people that are from a similar cultural domain. This reduces diversity and may, through this channel undermine effectiveness of groups. But not all diversity is per-se “good”.

An alternative of random assignment works well, but can create other issues such as teams without a balanced skill vector or talent pool. So I wanted to try something else. Create teams that are structured around the abstract concept of a high dimensional vector space in which human vectors that are represented in this high dimensional vector space are sufficiently diverse. That is, I want to identify groups from a large sample of individuals that are maximizing the spannable space in a latent space that may capture traits or skills.

Formally, if we think of latent traits and skills as being encodable in a vector, you want to create teams that can span a large vector space. Of course, there is an element to which it will be important to be able to interpret dimensions in such a vector space.

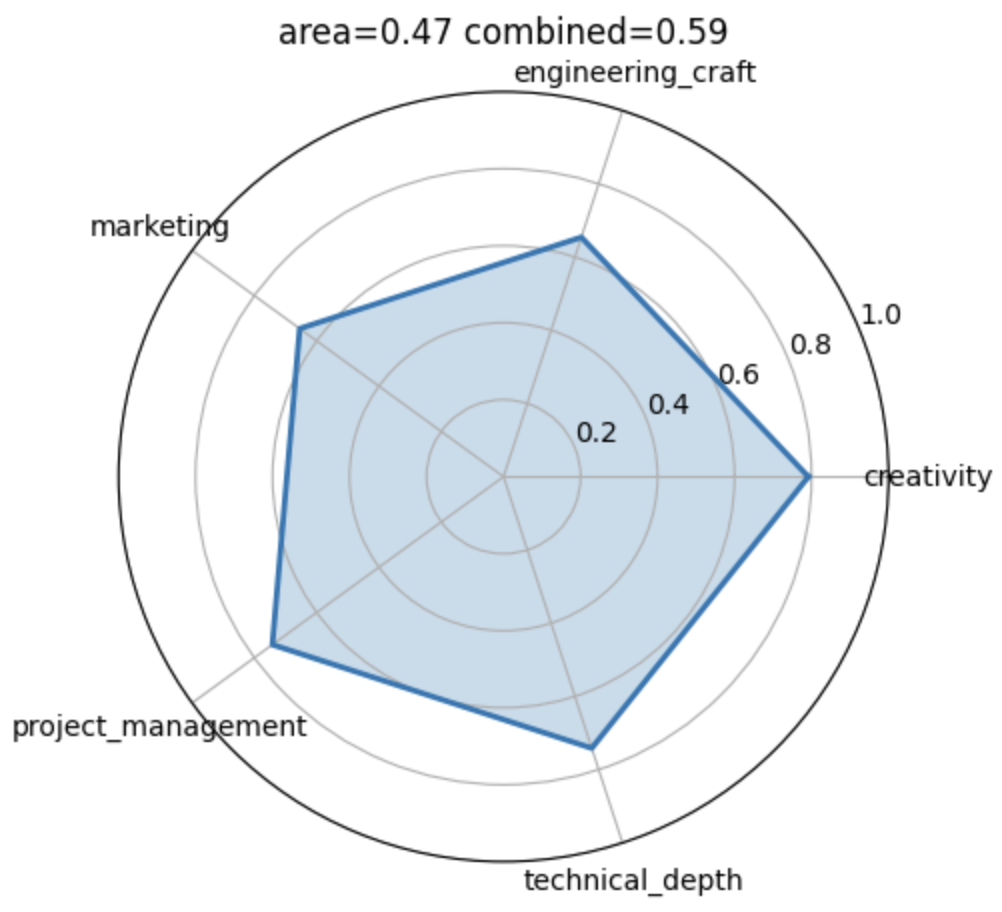

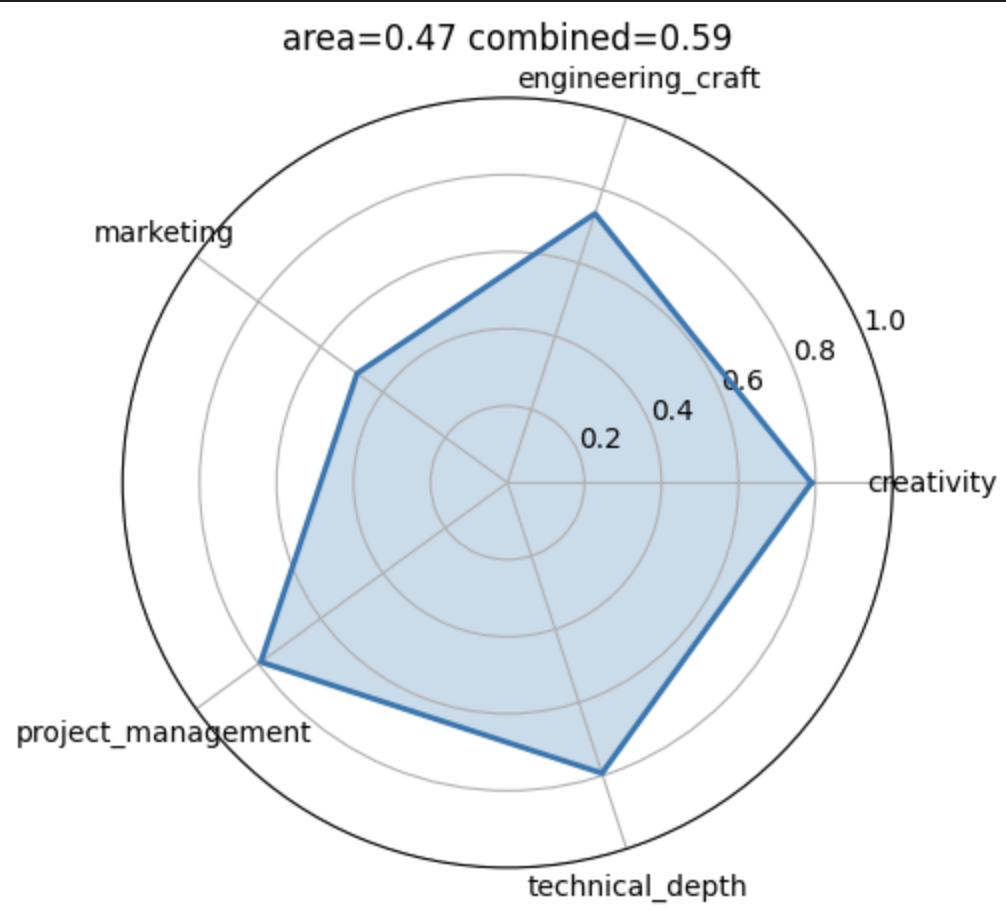

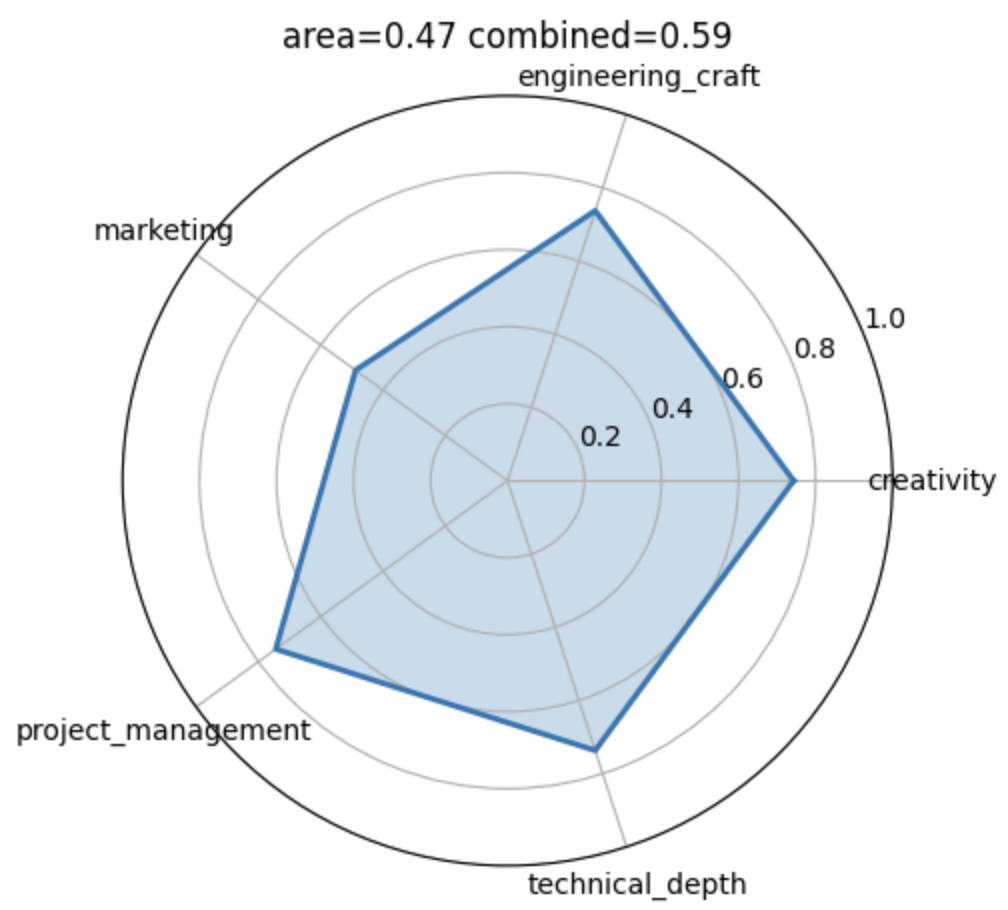

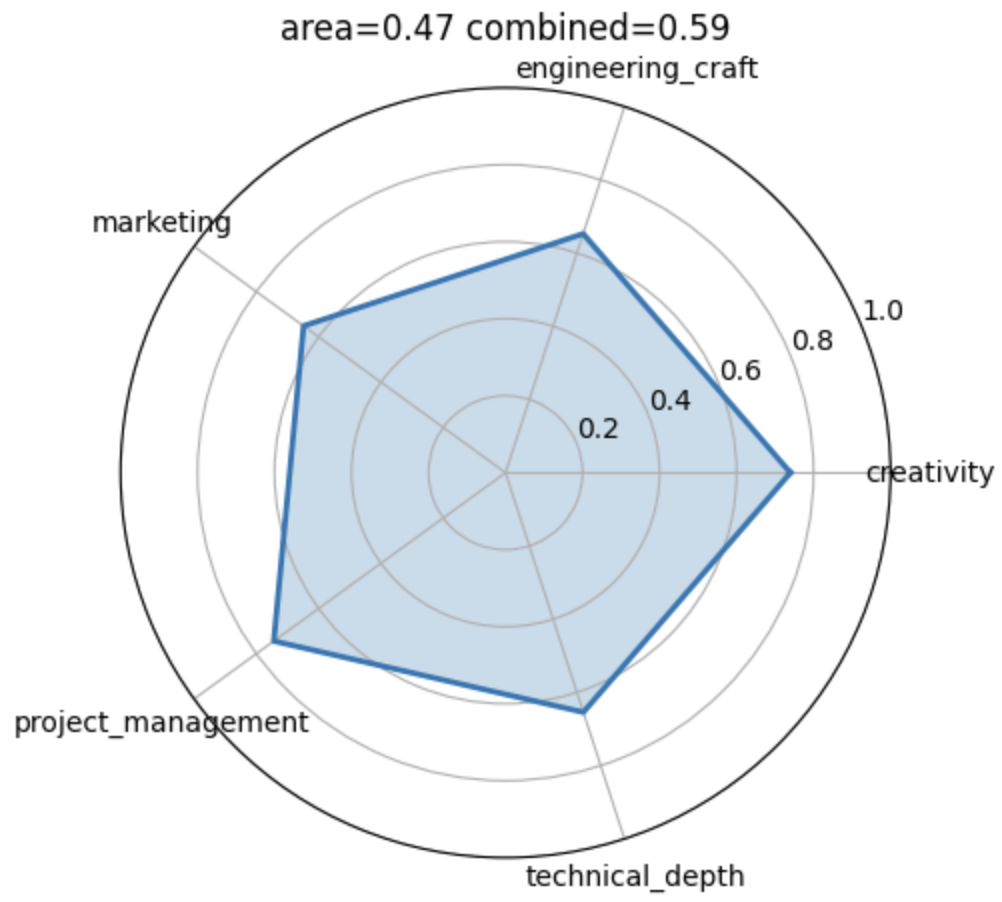

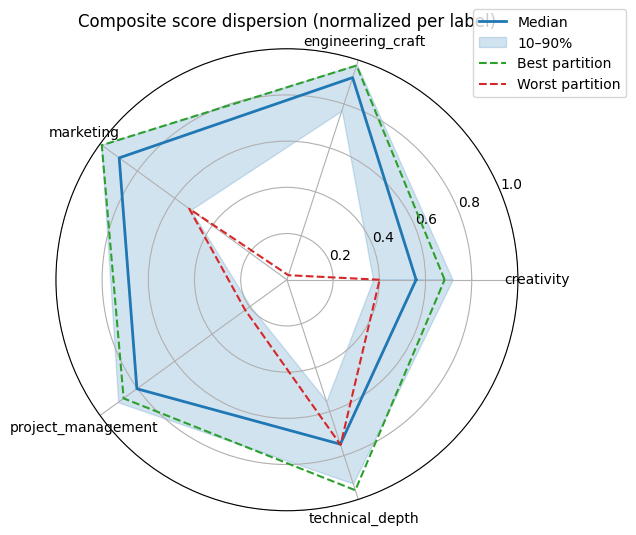

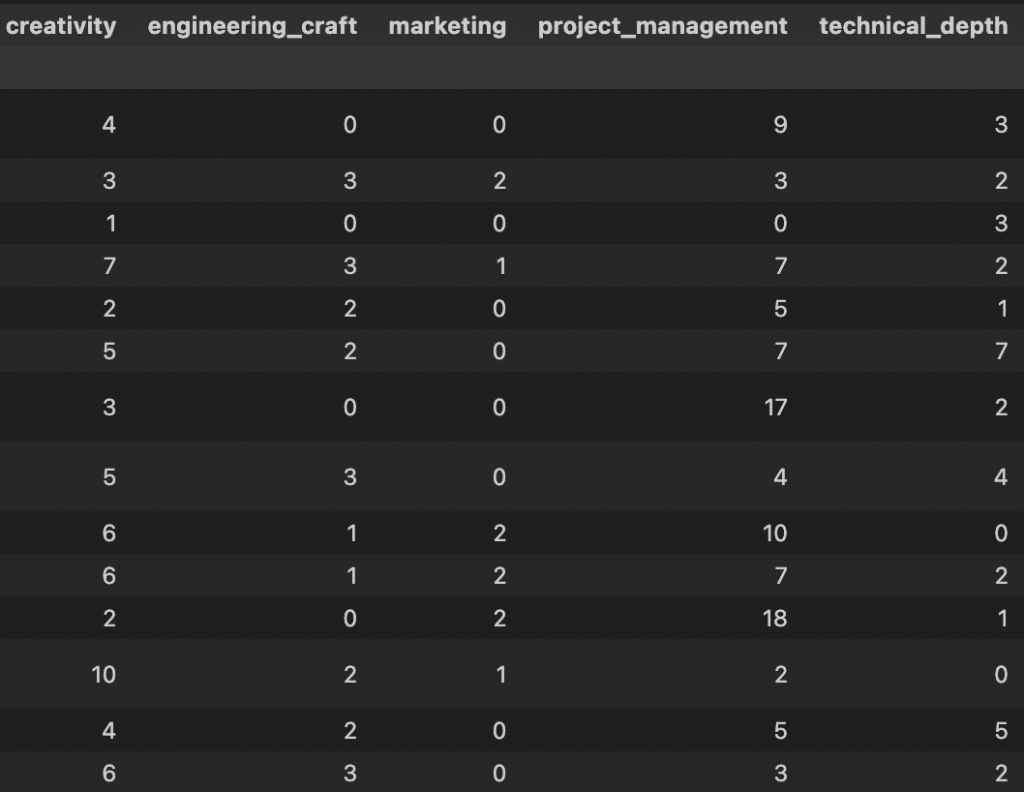

In order to do that I interviewed each student. I developed a quick interview protocol that aims to elicit three to five dimensions that I find relevant: technical depth/engineering depth, creativity, project management and marketing.

The idea is that, given that the group is relatively small just around 14 individuals, it should be feasible to create all potential draws of creating teams of size

The meetings were transcribed using my self-sovereign transcription tool. This produces diarized (that is, speaker specific) documents. The transcripts were then chunked and embedded using an open source embeddings model mxbai-embed-largest which yields a 1024 dimensional representation of the vectors. This was done using local Ollama installation (I am trying to champion open source AI due to the deep structural concerns I have covered elsewhere in my blog).

The embedding step is important as it may allow a comparisons in a semantically related space even though speakers draw from a different, but related vocabulary distribution when prompted along any of the dimensions that are covered. That is, it allows capturing similarities

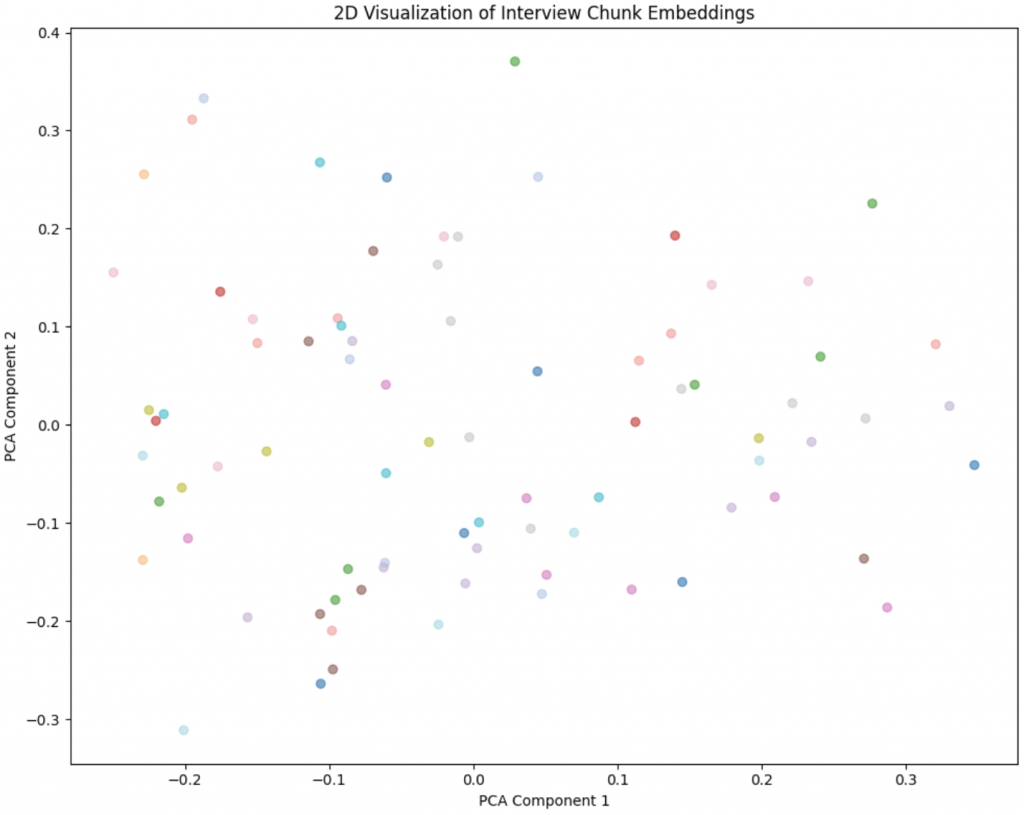

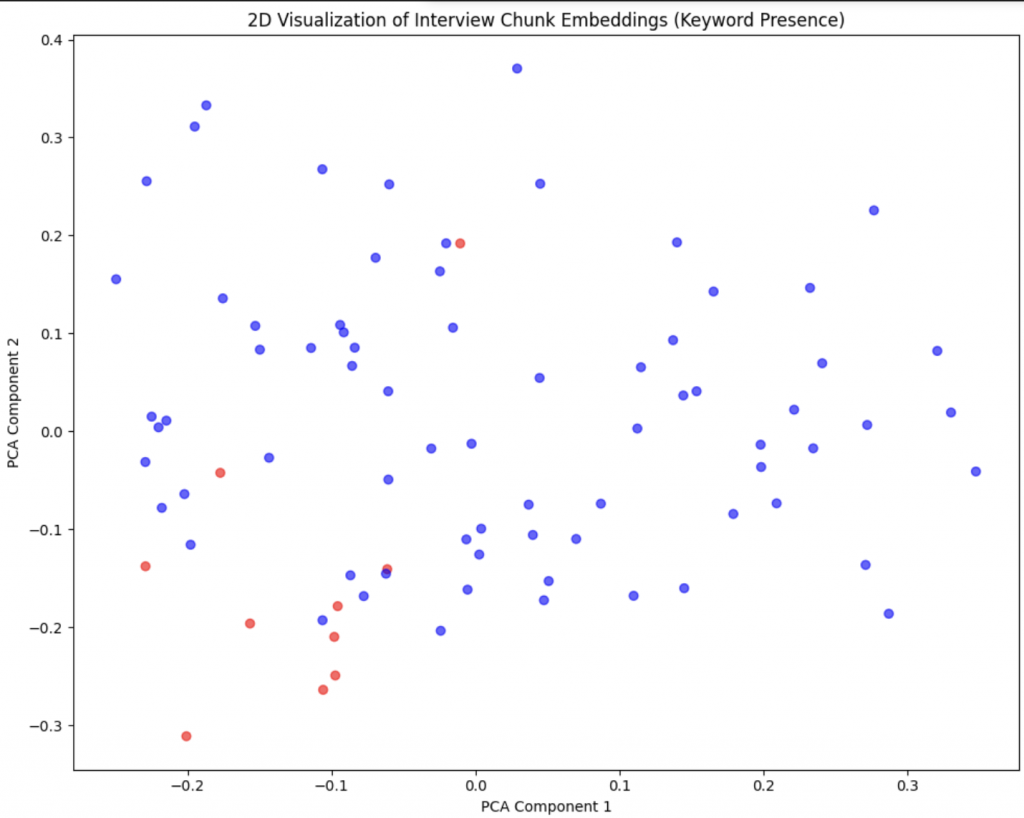

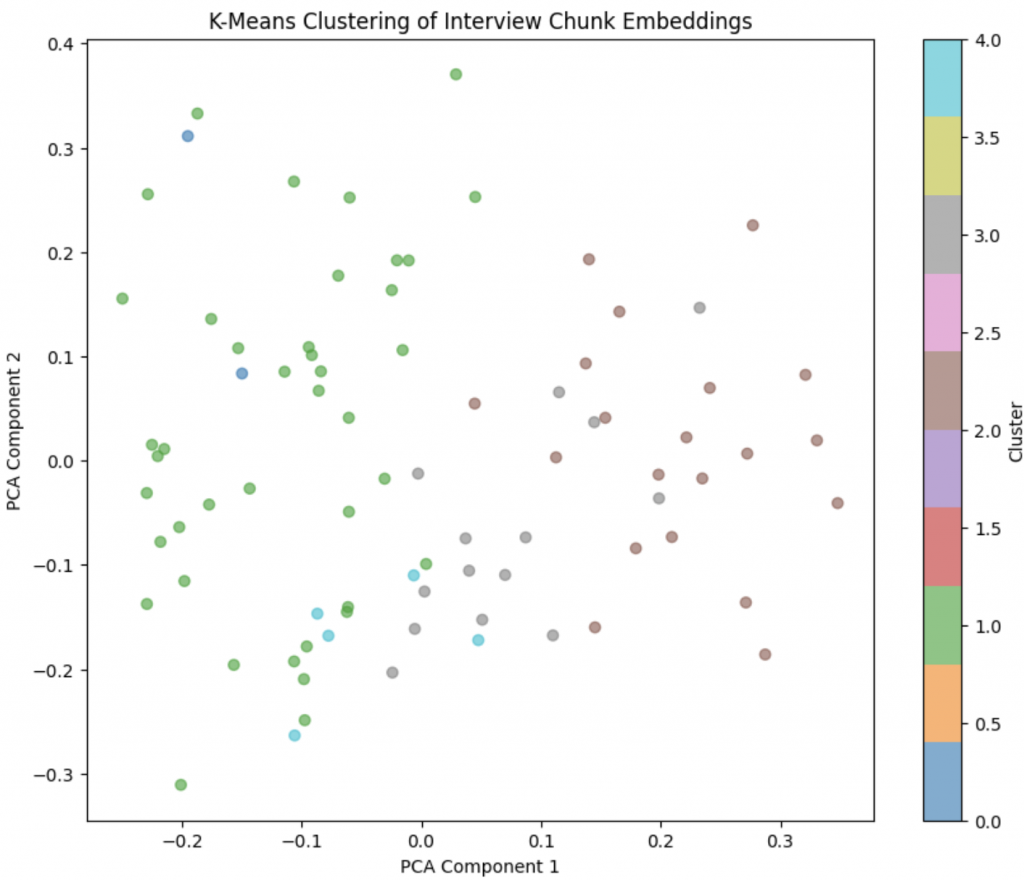

Below is an example output visualized in two dimensions on which I have then performed clustering. From left to right, we see that in two dimensions across the different data subjects/speakers, the points are quite scattered. This is because the present chunking strategy does not distinguish between the different dimensions of the interview as is illustrated in the second panel. There I colored points based on an ad-hoc classification of the chunk into different topic. We see that this is picking up some signal as there is a markable clustering of red points in the bottom right (these are chunks that talk about the same dimension/topic). Lastly I also looked at some K-means clustering but that is not super useful.

Creating the vector space dimensions

In order to cover the dimensions more appropriately, I next used

gpt-oss:20b and a prompt, again, locally deployed to classify the chunks into the four/five dimensions that I covered. The prompt assigns labels to each chunk. This helps in defining the concept vectors that are so relevant.

Definition of concept vectors

Using the above design I am now creating concept vectors that are the “global” defined concepts among all participants. That is, each of the dimensions now becomes defined in the embedding space as an, in essence, “average direction”. In some ways this conjoint vector is itself spanned by the contributions across the population here. Next comes the “group” design.

Group design

There is exactly two groups of size four and two groups of size three that can be constructed from the set of 14 names. What turned out to be a highly effective tool to illustrate the curse of dimensionality in this setting, which students so rarely grasp in depth, was the combinatorial problem of the allocation. People are completely dumbstruck when they dont guess that the “true” number is around 1 million possible ways to create such assignments.

We can then simulate all potential ways of creating these four groups and evaluate to what extend they span the five dimensional simplex. Below is an illustration of the empirical distribution across all potential allocations.

Among the sample of allocations that were spanning the simplex as broad as possible. Among the groups that are in the top 5%, I then drew a random sample. I am curious to see “how well this worked”. Below are the four groups.

I share the Jupyter notebook on github.